Hasanat Kamal

Update: 23:35, 28 October 2025

Wetlands Under Threat in Bangladesh – Initiatives to Protect

Baikka Beel Sanctuary. Photo - Hasanat Kamal

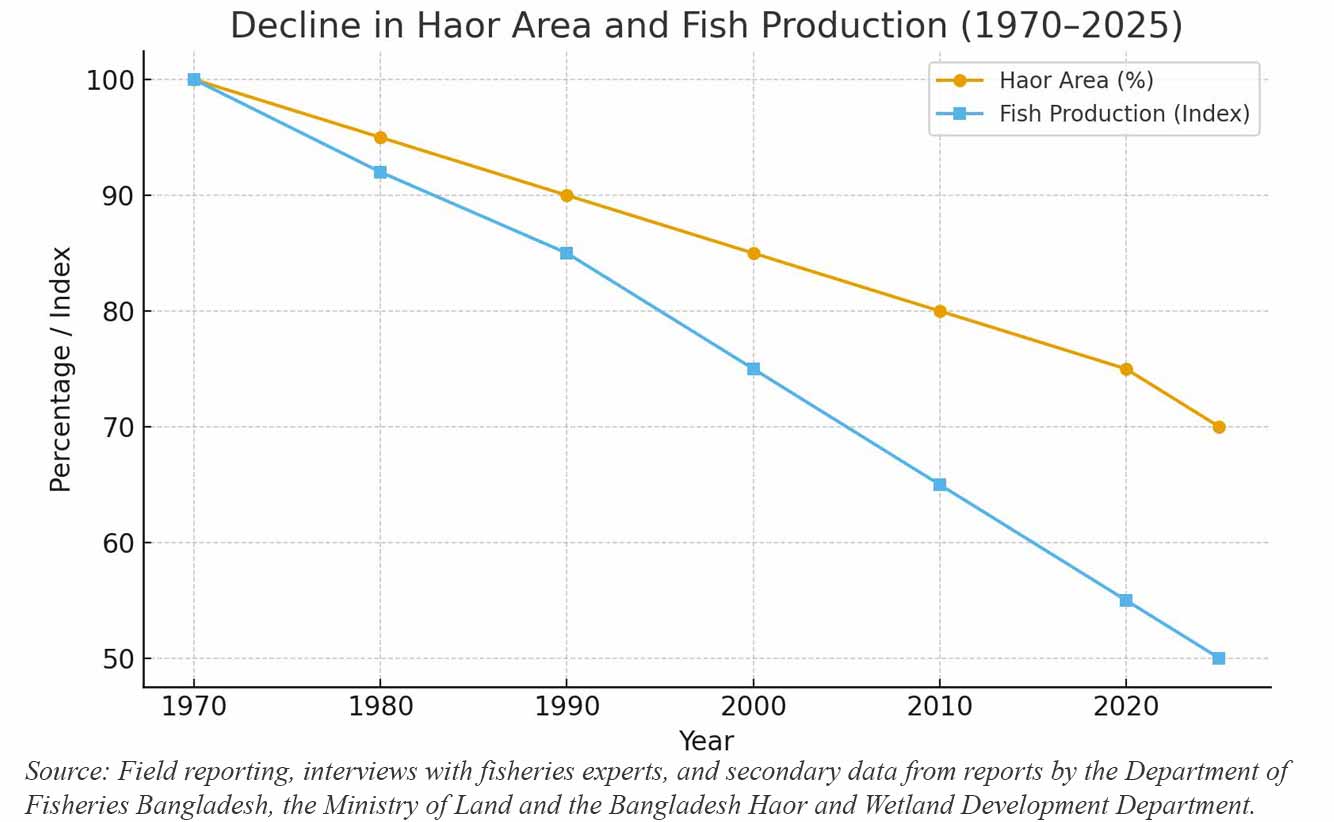

According to the Ministry of Land, Bangladesh has lost 70% of its wetlands in the past 50 years. These wetlands serve as crucial sources of freshwater, fish, and aquatic biodiversity. Agricultural land has also decreased by 30%. Rapid landfilling, encroachment, settlement expansion, industrialization, and urban growth have endangered haors and beels, putting biodiversity at risk. Wetlands are also being affected by flooding, drought, and climate change. Meanwhile, the country’s population has almost tripled.

Surprisingly, despite the decline in land area, rice and commercial fish farming have continued to expand to meet rising demand. However, environmentalists warn that this success in aquaculture is coming at the cost of destroying the natural character of the haor ecosystem.

-

Over the past 50 years, Bangladesh has lost 70% of its wetlands and 30% of its agricultural land.

-

Encroachment, landfilling, settlements, industrialization, and urbanization are pushing haors and beels toward extinction.

-

Biodiversity is under serious threat.

-

Floods, droughts, and climate change are severely impacting wetlands.

-

The country’s population has nearly tripled in five decades.

-

Despite the loss of land, rice and commercial fish production have sharply increased — posing risks to natural wetlands.

-

Community-led models like the Baikka Beel Sanctuary and local initiatives such as the Lachidhara canal re-excavation are showing ways forward.

In this situation, community-based conservation in Bangladesh is showing hope. The Baikka Beel Sanctuary in Moulvibazar — established and maintained by local communities — has become a safe haven for fish, birds, aquatic plants, and wildlife. Experts believe Baikka Beel could serve as a model for wetland conservation. Similarly, community-driven initiatives such as the rehabilitation of Kodalichhara, the bird-shelter villages, and youth-led re-excavation of Lachidhara canal are opening new paths for wetland sustainability.

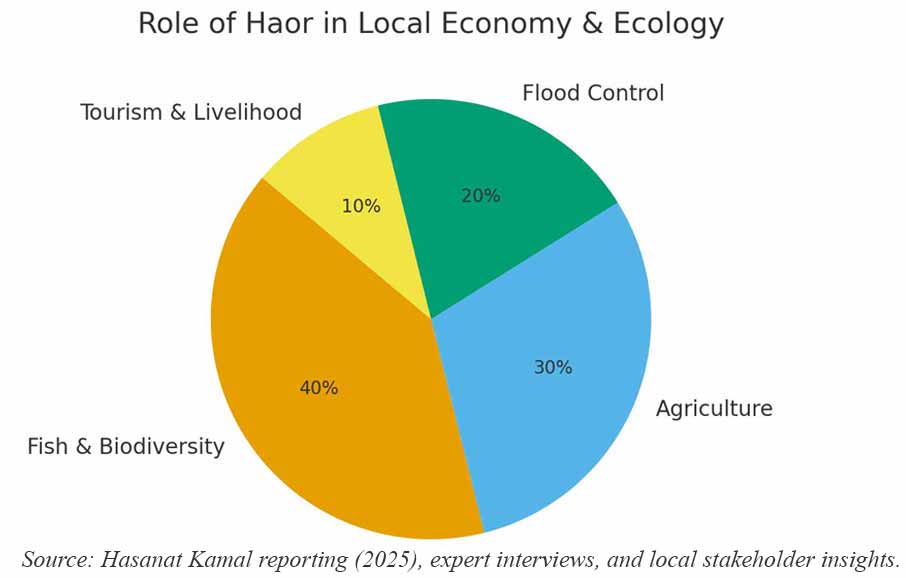

A haor is not just a source of fish or agriculture; it is a reservoir of water, crucial for flood control, biodiversity conservation, and food security. — Wetland Expert Prof. Monirul H. Khan

This report by Hasanat Kamal for eyenews.news, supported by the Internews Earth Journalism Network, explores how wetlands and farmlands are under growing pressure — and how sanctuaries like Baikka Beel offer hope. The story captures voices of local fishermen, farmers, youth, women, indigenous groups, environmentalists, and government officials.

Moulvibazar, a key district in Bangladesh’s northeastern Sylhet Division, hosts the highest concentration of wetlands and haors in the country. The Hakaluki Haor, the largest haor in Asia, lies here. Numerous other haors and beels spread across Sunamganj, Habiganj, Sylhet, Kishoreganj, Brahmanbaria, and Netrokona districts. Experts describe these areas as rich in agriculture, fisheries, birds, aquatic vegetation, and biodiversity.

Hakaluki Haor, one of the largest wetlands in Bangladesh, filled with water during the monsoon. Photo: Md Amir

However, these wetlands are gradually vanishing — due to climate change, natural factors, human greed, and unplanned industrialization. Despite the threats, numerous community and conservation initiatives are emerging — offering a glimmer of hope for Bangladesh’s disappearing wetlands.

Haors used to teem with fish — shol, gozar, tengra, puti, and many others. Now there’s no fish, not even fingerlings. Where water once flowed, cattle now graze.— Fisherman Katu Mia

Bangladesh’s Haor and Wetland Regions

During the monsoon, the haor basins of Bangladesh brim with water; in winter, migratory birds gather in flocks. Throughout the year, these wetlands remain vibrant with fish, aquatic plants, and biodiversity.

Across seven districts, there are over 400 haors, including the well-known Hakaluki, Tanguar, Hail, Kawadighi, Shuni, and Boro Haors.

A part of the flooded swamp forest of Hakaluki Haor during the monsoon. Photo: Hasanat Kamal

Hakaluki Haor: Gradually Filling Up

There were prolonged floods in 2024 and 2018, but in 2021, the haor didn’t receive any water at all. This is how floods and droughts alternate in Bangladesh — local farmers

Hakaluki Haor, the largest freshwater wetland in Asia, is gradually silting up. Local fishermen and farmers say the haor can no longer hold water like before. During the dry season, most of its areas turn into arid land, while in the monsoon, excess water spills over into nearby villages, causing floods and long-term waterlogging.

Climate change has left its mark here. In some years, monsoon floods submerge the haor and nearby rivers; in others, the land remains parched and people struggle for water.

During a recent visit to Hakaluki Haor in July 2025, an unusual scene unfolded — there was a shortage of water even in the monsoon. In Gourkoron village of Kulaura upazila, vast stretches of land that should have been under water lay dry. Along the muddy road, Katu Mia, a man in his sixties, was walking with his small triangular fishing net, known locally as Fellun Jal.

Asked why there was no water at this time of year, he replied `The road we’re standing on should be neck-deep under water now. There used to be plenty of fish — shol, gojar, tengra, puti — but now there are none, not even fry. Cows and buffalo graze where fish once swam.'

About a mile and a half away, at Islampur Mohona, fish traders were waiting for fishermen to bring their catch from the haor. But even by evening, most boats returned empty. Some carried only a few small shrimps and baby fish. `There’s no water, so there’s no fish. That’s the reality of Hakaluki now. One year we face drought, the next brings devastating floods', said Karim Mia, a 65-year-old fisherman.

Journalist Hasanat Kamal talking with fishermen and fish traders at Islampur estuary of Hakaluki Haor. Photo: Md. Mostafa

Local farmers and fishermen recalled that the floods of 2024 and 2018 submerged villages across Kulaura, Juri, and Barlekha upazilas, affecting hundreds of thousands of people and causing massive losses. But in 2021, the haor received almost no water at all. These patterns, they said, reflect the worsening cycle of flood and drought across Bangladesh. Environmental activists have renewed their call to declare Hakaluki Haor a Ramsar site to ensure stronger protection for this vital wetland ecosystem.

Read More: Feature - Kodalichhara: A Story of Transformation

Crisis in Kawadighi Haor

I can’t even catch 200 taka’s worth of small fish after roaming the haor all day. One year everything drowns in floods, the next it all dries up. How can we survive like this? — Kadam Ali, local fisherman

Kawadighi Haor, one of the most important wetlands in Moulvibazar district, was once known for its fertile land that produced both rice and fish. But local farmers say production has dropped sharply due to irrigation shortages and heavy siltation, as the haor continues to fill up with sediment.

A field visit in late July and early August revealed an alarming sight — vast areas of dry land where water should have been flowing during the monsoon. At the site, Kadam Ali, a fisherman from the area, described the transformation- `In this season, the haor should have waist-deep or chest-deep water in some parts, even deep enough for swimming in others. It should be covered with lilies and lotuses, with boats gliding through the flooded fields. Fish would jump in the waves — puti, chanda, darikana, shol, gojar, taki — schools of colorful fish everywhere. Now the haor is half dry. There’s hardly any water. No fish, no fry, only barren land.'

He expressed frustration and despair- `I can’t even earn 200 taka after fishing all day. One year the floods destroy everything, the next we face drought. How do we live?'

By mid-August, however, the haor had finally filled with water after delayed rains. Yet local fishermen and farmers warned that this late arrival of water would negatively affect fish breeding, aquatic plants, and biodiversity.

Former Moulvibazar District Fisheries Officer Emdadul Haque said `The situation reflects the severe impact of climate change. Siltation is worsening, and the haor’s natural capacity to retain water is declining.'

A view of Kawadighi Haor. Photo: Ranjit Jony

The Puber Haor (Boro Haor) and Broken Dreams

The Puber Haor, part of Boro Haor, a vital wetland in the western part of Moulvibazar Sadar, has long been a fertile source of both rice and fish. Nearly 100,000 people depend on this haor for their livelihoods. But today, they are watching their farmland and water bodies vanish before their eyes.

The solar panel project under construction in the Athangiri Puber Haor, part of the Boro Haor — once a vast stretch of paddy land that sustained thousands of people in the surrounding agrarian villages for centuries. Photo: Abdur Rob

Bachhu Mia, a middle-aged farmer from Athanagiri village, said - this haor is part of our life and livelihood. Ninety-eight percent of the people in our village are farmers. Without the rice from this haor, people will face famine. Now everything seems to be arranged to stop rice cultivation here. A solar power project is being built in the haor. It’s not only destroying rice fields — even grazing cattle and goats has become impossible.

Elderly resident Kanai Mia, from the same village, added with deep concern- now there are houses inside the haor. Companies are coming in and setting up projects. Everything is changing before our eyes!

The Gopla River, which flows beside Puber Haor, is also shrinking due to siltation and riverbank erosion. People who depend on the haor — farmers, fishers, and herders — are witnessing the rapid disappearance of their natural lifeline. Environmentalists and biodiversity conservationists have also raised the alarm.

The Gopla River in Moulvibazar Sadar Upazila is narrowing due to erosion and siltation. Photo: Hasanat Kamal

Khasru Chowdhury, Member Secretary of the Moulvibazar Haor Movement, warned- If this haor cannot be saved, we will not only lose 230 species of fish, but also our biodiversity and natural ecosystem. Establishing a solar power plant inside the haor is nothing short of a suicidal decision.

Bangladesh Could Sink Underwater, Warns Haor Researchevr

Bangladesh sits on a tectonic plate that could fracture under the pressure of rising water, eventually submerging the country beneath the Bay of Bengal. -Sajal Kanti Sarker, a haor researcher from Sunamganj

During the dry season, most of Bangladesh’s haor lands crack open like this. The photo was taken at Tanguar Haor, Sunamganj. Photo: Hasanat Kamal

He believes that attempts to urbanize or fill the haors — vast wetlands in northeastern Bangladesh — coud have catastrophic consequences. If the haors are filled, saline water from the sea will intrude inland, contaminating freshwater sources. Groundwater will turn salty, arsenic levels will rise, and safe drinking water will vanish, he said.

Sarker explains that Bangladesh’s hills are connected to the sea through underground river networks. As wetlands disappear, flash floods from the hills will intensify, destroying homes and croplands.

He further warns that continuous pressure from water could cause a tectonic shift — Eventually, the earth’s crust under Bangladesh could rupture, submerging the land into the Bay of Bengal.

However, Malik Fida Abdullah Khan, water resources engineer and Director at the Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services (CEGIS), partially disagrees. He notes that haor lands lie only 3–4 meters above sea level and are sinking at a rate of 2–4 millimeters per year. Rising sea levels may cause prolonged flooding in the Meghna basin, he cautions.

Meanwhile, geologist Prof. Syed Humayun Akhter of Dhaka University dismissed the tectonic collapse theory as a personal opinion, saying there’s no scientific evidence to support it.

Read more: Consequences and Implications of Climate Change for the Haor Region: Malik Fida A. Khan

Public Health Impacts of Pesticide Use

Sajal Kanti Sarker said that the indiscriminate use of pesticides without any public awareness is destroying biodiversity — especially aquatic plants and other forms of life. This will have serious consequences for public health. Haor farmers will be the most affected by cancer. The risks of heart disease, skin disorders, and respiratory problems are also increasing, he warned. The haor researcher emphasized the need to find safer, eco-friendly pest control methods and to raise awareness about the harmful effects of pesticides.

Baikka Beel Sanctuary - A Model for Wetland Conservation

While the protection of haors and wetlands in Bangladesh has become a matter of grave concern, the Baikka Beel Sanctuary in Hail Haor, Moulvibazar, stands out as a successful example of wetland conservation. According to government records, the 100-hectare Baikka Beel was declared a sanctuary in 2003 to preserve fish, aquatic plants, and biodiversity. It is managed under a co-management system by local residents through the Borogangina Resource Management Organization.

Baikka Beel, a co-managed sanctuary rich in aquatic plants and biodiversity. Photo: Md Amir

Labbek Majhi, a resident of a nearby village, said, This beel is home to many fish species such as Chital, Boal, Madhu Pabda, and various types of carp. These fish breed here and spread throughout the haor. We have even preserved fish weighing 30–50 kilograms. It’s us, the locals, who guard the sanctuary — though it’s often difficult to stop illegal fishing and hunting of birds.

Nature photographer and environmental conservationist Khokon Thounaijam said, This beel hosts numerous species of local and migratory birds, aquatic plants, and swamp forests that sustain wetland biodiversity. Sanctuaries like Baikka Beel are vital for our ecosystem. Conservation should be led by local communities with the joint effort of environmental activists, administration, the Fisheries Department, the Department of Environment, and local representatives.

However, Thounaijam also pointed out some challenges- there are only three guards to protect this vast wetland, which is far from sufficient. Poachers often cast fishing nets under the cover of darkness and collect them by morning. Even during the day, they exploit natural resources while evading the guards.

Professor Monirul H. Khan, wetland specialist and Chairman of the Department of Zoology at Jahangirnagar University, emphasized, Baikka Beel is an excellent model for haor conservation in Bangladesh. Through local participation and co-management, fish production across the entire haor has increased significantly because mother fish can live and breed safely there — and the local people are the ones benefiting. This model could be replicated in other haors and wetlands across the country.

Canal Restoration Revives Life in Binnar Haor

The Lachidhara Canal, located in Binnar Haor of Moulvibazar Sadar upazila, was once clogged and encroached upon, leaving farmlands barren and destroying the natural breeding grounds for fish. However, a group of local young entrepreneurs have transformed the fate of this haor. With the cooperation of journalists and local administration, they freed the government-owned canal from illegal occupation and excavated it during the dry season in 2022.

Binna Haor revived after the excavation of the Lachidhara Canal. Photo: Hasanat Kamal

One of the initiators, Jahed Ahmad Chowdhury, said, Today, the Lachidhara Canal has turned into a water reservoir connected directly to the Kodalichhara stream. Farmers now have access to irrigation water. Fields that once produced a single crop are now yielding three to four crops a year. Alongside high-yield rice varieties, traditional local ones like Binni and Moynashail are also being cultivated. Farmers are growing vegetables, wheat, and maize too. Indigenous fish species such as koi, shing, magur, and tengra — which had disappeared for decades — have returned. The area is now teeming with birds and plant diversity. Educated young farmers and expatriate entrepreneurs are being drawn back to the haor by this agricultural revival.

Read More: Farmers’ Dreams Revive in Binnar Haor Through Youth Initiatives

Voluntary Road Repair in Athangiri Haor

Zakaria Ahmad Shahi, a young man from Athangiri village in Moulvibazar Sadar upazila, shared that around 7,000–8,000 people live in their village, with nearly 95% depending on agriculture. Due to years of neglect, the main access road to the haor had become unusable, and no government initiative or funding was forthcoming. In response, villagers collectively raised around 150,000 taka and repaired the road themselves, with many volunteering without pay. This was a community effort, Shahi said. We repair our haors, canals, and wetlands through such collective actions. A few years ago, villagers also excavated parts of the Fola River voluntarily to conserve water, which now helps irrigate fields during the dry season and provides water for livestock.

A Public Pond for Villagers

Zakaria Ahmad Shahi also pointed out that ponds and wetlands are rapidly disappearing across the country. There’s a growing trend of filling up ponds to build structures, which reduces access to water for daily needs and livestock, he said. Our ancestors preserved public ponds for community use. While others are filling theirs, six to seven families in our village have renovated and reopened ours. If all ponds disappear, where will the villagers go for bathing, household chores, or watering animals?

Water Flow Restored in Kodalichhara Through Social Action

Kodalichhara, the only natural drainage canal for Moulvibazar town, had once become clogged with plastic, polythene, and urban waste due to lack of maintenance. The canal’s blockage caused flooding throughout the town, with its waste eventually flowing into Hail Haor and the Gopla River.

The previous condition of Kodalichhara. Photo: Hasanat Kamal

After the renovation of Kodalichhara, the town no longer experiences waterlogging. Photo: Md Mostafa

Young social activist Dora Prentice recalled, Restoring Kodalichhara was a long-cherished dream for the townspeople. We had to wait decades for it to come true. Eventually, a group of young people formed a Facebook group called ‘Gorbo Shopner Shohor’ (Let’s Build the City of Dreams) and launched a campaign. It grew into a social movement. The Moulvibazar Municipality took the initiative, joined by almost all local social, cultural, and volunteer organizations, public and private institutions, schools, colleges, madrasas, and political activists from all parties. On February 10, 2018, a massive voluntary cleanup and excavation of Kodalichhara began. Later, the municipality continued restoration and beautification work. Now, water flows freely through the canal, boats move during the monsoon, and the town no longer suffers from waterlogging. What was once a curse has become a blessing.

Local residents believe the restoration of Kodalichhara proves that environmental protection is possible when communities unite through social initiatives and public participation.

Bird Sanctuaries in Haor-Side Villages

In Malliksarai village of Moulvibazar Sadar upazila stands the home of Mujahid Ali — locally known as a bird house. Surrounded by bamboo groves and trees, his yard has become a haven for thousands of birds — from white egrets to cormorants.

These are our guests, Mujahid Ali said. They stay here all year round. We make sure no one harms or hunts them. Their droppings sometimes damage trees and rooftops, but we don’t see that as a problem.

Rezaul Karim Chowdhury, who served as the Divisional Forest Officer of the Moulvibazar Wildlife Management and Nature Conservation Division for about three years, said, There are several such bird houses in the haor-side villages of this district, where birds find safe shelter. From my visits to remote areas, I’ve seen that people have become much more aware — they now see wildlife as their friends.

At Malliksarai village, located in the Kawadighi Haor area, Mujahid Ali’s house has become a shelter for white egrets and various other bird species. Photo: Md Mostafa

According to the Forest Department, houses like Manohar Master’s in Halla village of Barlekha, Ataur Rahman’s in Kagabala of Sadar upazila, and Nurul Islam Ponki Mia’s in Biriimabad village, along with 8–10 other homes across the district, have become safe sanctuaries for thousands of birds. Many of these birds build nests there and hatch their eggs — turning private homes into thriving micro-habitats of biodiversity.

Social Movement to Protect Haors from Industrial Encroachment

Several industrial groups are setting up large-scale solar power projects in the haor wetlands of Moulvibazar, which locals and environmental activists warn could severely harm these delicate ecosystems. Concerned citizens have submitted memorandums to the district administration and are regularly holding human chains under the banner of Haor Rokkha Andolon, Moulvibazar (Save the Haor Movement, Moulvibazar).

M. Khusru Chowdhury, the organization’s member secretary, said, From what we’ve learned, solar panel projects have been established on 900 acres in Kauwadighi Haor, 300 acres in Hail Haor, 100 acres in Sikrail, and in parts of the Borhaor area of Athangiri. But the land acquired or occupied for these projects far exceeds what’s necessary. Setting up solar power projects inside haor zones without consulting haor experts is a suicidal decision.

He added that local communities continue to organize and protest to protect the haors, believing that safeguarding these wetlands is essential for their survival and for future generations.

Read more: Farmers protest solar power project on farmland in Moulvibazar

Youths in Biodiversity Conservation

Environmentalists and biodiversity conservation activists believe that Bangladesh’s wetlands are a unique reservoir of biodiversity. However, news reports often show that wild animals, including snakes, enter human settlements, where they face danger, injury, or even death. To rescue such wildlife, social awareness has been growing. A voluntary organization called Stand for Our Endangered Wildlife (SEW) was established by a group of young people from Sreemangal upazila of Moulvibazar district. They work to rescue and rehabilitate endangered birds, snakes, and other wild animals from various wetlands, forests, and human habitations in the Sylhet region.

SEW members rescuing a Pangolin. Photo: Eye News

One of the organization’s founders, Sohel Shyam, said, In the past eight years, we have rescued more than one thousand birds, snakes, and wild animals through this organization, provided necessary treatment, and released them back into nature. These include fishing cats, slow lorises, pangolins, pythons, owls, and crested serpent eagles, among others.

Sohel Shyam added, We also carry out awareness activities. We are doing everything with our own money. Environmentalists believe that the efforts of these conscious young people demonstrate how local initiatives can effectively protect biodiversity.

Women’s Role

The foundation of agriculture is built within the household, and women do it all. Now women also go directly to the fields. — Sajal Kanti Sarkar

Haor researcher Sajal Kanti Sarkar said, Men survive through the labor of women. Rice is not produced just by planting. Women are involved in seed preparation for paddy and winter crops, seedbed preparation, planning, motivation, timing, supervision, and even tasks like bringing cattle to the field, along with all household chores.

Women in the haor region of Sylhet are busy drying paddy and straw. Photo: Hasanat Kamal

The researcher, who grew up in the haor region of Sunamganj, said, Women in remote areas used to work directly in the fields, and they still do so today. They dry straw and paddy, boil rice, and handle post-harvest work. In marginal areas, it is the women who cultivate winter crops. It was women who first collected wild seeds and began agriculture. Women are the creators of agriculture, and they still remain so.

Professor Monirul H. Khan said, In the case of wetlands, women have a close connection. Men may catch the fish, but from cutting and cleaning the fish to all other household work, it is the women who do everything.

Haor-Based Ethnic Communities

Haor researcher Sajal Kanti Sarkar said, In areas such as Sunamganj, Kishoreganj, and the Kalmakanda and Durgapur upazilas of Netrokona, there are still some indigenous communities whose lives and livelihoods are centered around the haor wetlands. These include the Garo, Hajong, Banai, and Koch communities. Once, there were also Kuki-Naga Kuki people, but they are no longer there — they used to live by hunting. There used to be the Bede community as well, but they have also disappeared. Besides, in the Moulvibazar and Habiganj regions, there are Manipuri communities who depend mainly on agriculture.

Sajal Kanti Sarkar further said, These ethnic groups are engaged in rice cultivation, winter crop production, and fishing. In the past, these marginalized groups made fishing tools such as chai, paron, dori, and polo using bamboo sticks and cane. They also made agricultural tools like baskets, ploughs, and yokes from bamboo and wood for their livelihood. But now, with the mechanization of agriculture, the demand for these traditional tools has almost disappeared. Around 40 to 42 species of bamboo are found in this region. In earlier times, people lived in bamboo and thatch houses, and many household items were made of bamboo. Now, as brick houses have become common, the demand for bamboo has declined.

Unprecedented Success in Rice and Fish Farming, but Concerns Over Wetland Conservation

Bangladesh has seen a remarkable increase in rice and fish production — several times higher than before. According to government statistics, the country now has a surplus in both fish and rice production. Yet, wetlands are disappearing; agricultural lands are shrinking, population is increasing, and more settlements are being built. Environmentalists, however, have warned that behind this apparent success in fish farming, the very nature and essence of the haor ecosystem may be destroyed.

Importance of Using GIS Technology

Wetland expert Professor Monirul H. Khan believes that wetland management in Bangladesh can be significantly improved through the use of GIS-based satellite monitoring and data-driven observation technology. He said, through satellite mapping, we can observe the seasonal changes of Bangladesh’s haors and beels (wetlands). We can also monitor whether any encroachment is taking place. Even more advanced technologies are now available — we can monitor water quality, and use drones for patrolling. It’s possible to easily track if anyone is fishing illegally or if unauthorized boats are entering the wetlands.

He added, some technological tools are already being used in the forest and biodiversity sectors, but not much in wetlands — this definitely needs to be implemented.

The Potential of Wetlands

Haor researcher Sajal Kanti Sarkar believes that conserving Bangladesh’s wetlands is quite achievable. He said, the life of wetlands depends on rainwater. That rainwater is still unpolluted. The natural cycle that sustains haors is the flow of rainwater from hills, waterfalls, and rivers. We can easily preserve that if we want — because with modern machinery, dredging or re-excavating haors, beels, and rivers is now very easy.

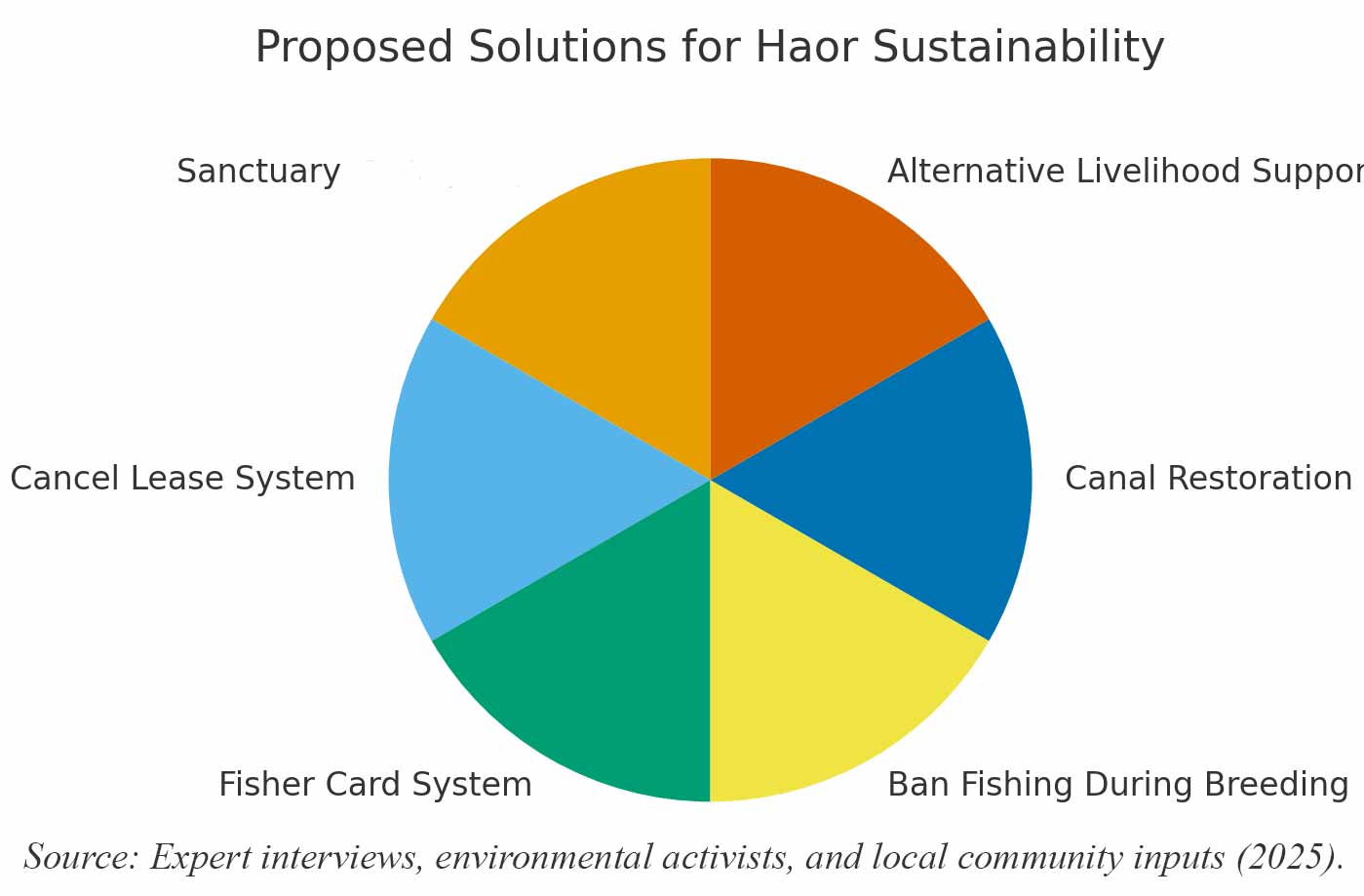

Recommendations from Local Fishers, Farmers, Environmentalists, Journalists, Wetland Experts, and Researchers for Wetland Conservation:

Actions to be Taken —

- Excavate wetlands and maintain navigability.

- Avoid altering the natural character of haors.

- Establish fish sanctuaries by involving local fishers and farmers.

- Stop leasing out beels.

- Enforce strict laws to prevent the catching of brood and juvenile fish during breeding seasons.

- Provide incntives to fishers during fishing ban periods.

- Use GPS monitoring and information technology for surveillance.

- Stop constructing high embankments around haors.

- Initiate programs to conserve aquatic plants and trees.

- Develop nurseries for aquatic plants.

- Introduce agricultural insurance for wetland-dependent farmers.

- Establish dedicated haor research centers.

- Ban the use of harmful pesticides.

- Preserve the region’s mystical (Baul–Marami) heritage and culture.

- Promote eco-tourism initiatives.

Haor Master Plan

Regarding the challenges, necessary actions, and planning, the Haor and Wetland Development Directorate stated that a draft master plan has been prepared focusing on the socio-economic development of the haor region, agriculture, fisheries, biodiversity conservation, environmental and wetland management, infrastructure development, and addressing climate change–related risks. This draft has been opened for public opinion and suggestions. Anyone can share their views regarding this master plan.

However, wetland researcher Sajal Kanti Sarkar said, This is not really a master plan. There are many flaws. We will sit and review it. We will give recommendations on what additions or deletions can be made. They may or may not consider our opinions.

Conclusition

Amid the severe crisis of wetlands in Bangladesh, initiatives like the Baikka Beel sanctuary, voluntary excavation of Lachidhara Canal, renovation of Kodalichhara, and Pakhibari (bird houses) projects offer hope. Wetland experts emphasize expanding such initiatives nationwide by ensuring community participation and declaring some wetlands as protected areas. They also believe that strict enforcement of laws, along with the use of advanced technologies such as satellite mapping and GIS, will pave new ways for wetland conservation.

Note: This article was originally published in Bengali on eyenews.news and has been translated into English by the author.

-

Read the story in Bengali: হুমকির মুখে জলাভূমি – বাংলাদেশের হারিয়ে যাওয়া হাওর ও বিল রক্ষার উদ্যোগ

- Bear Grylls announced to become a forest dweller

- Wetlands Under Threat in Bangladesh – Initiatives to Protect

- Alberta declares state of emergency over wildfires

- Deer rescued with legs tied in Habiganj

- The Untold Stories: Indigenous Rights, Climate, and Social Justice

- Satellite on Fishing Cat Body (Video)

- Satellite on Fishing Cat in Moulvibazar (Video)

- Farmers’ Dreams Revive in Binnar Haor Through Youth Initiatives